Context

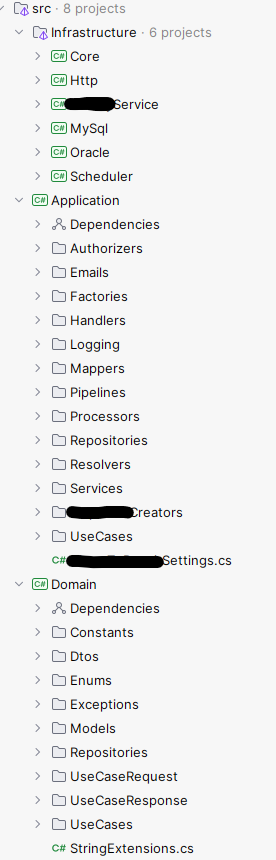

Some of the most common codebase structuring patterns I have seen in .NET space resemble these:

I call them “Level 0” because they organise code by technical layers mostly. They are not necessarily wrong or bad, and up to a certain level of complexity might even be fine or if the system is already a single purpose system then additional structure won’t likely add much value.

In slightly more complex systems I have also seen what I call “Level 1” variant with some conceptual separation which makes boundaries a bit clearer than Level 0:

But in general I see a few problems with all these structures:

- Business capabilities are often spread across low level technical layers, so, hard to understand what capabilities does a system support. Requires navigating a couple of levels of structure to find that out

- Changes often ripple across layers and across solution, sometimes leaking into other areas of the system which creates possibilities for unintended side-effects

- Harder for new team members to get up and running as they spend time trying to figure out where does code for a specific functionality live

- High risk of violating module boundaries by taking inappropriate dependencies, this also makes future distribution more risky and considerably high-effort

Our ongoing struggles with understanding and creating good module boundaries, can often trigger a fear of being stuck with monolithic designs and lead us towards microservices prematurely increasing accidental complexity, cost and cognitive load. The existing solution structuring patterns often don’t help the matter either, in fact, they can make it easy to make modularity errors which can lead “monolith bad, microservices good” kinds of reductive responses.

My goal with this post is to propose a model for structuring .NET monoliths in a modular fashion that both keeps distribution complexity low whilst at the same time keeping options for distribution in the future, open!

I call this model the Published Interfaces model that I have been developing and trying here and there for the last year or so, having taken inspiration from various sources:

- Martin Fowler’s IEEE paper that introduced me to the idea of “published” interfaces

- Simon Brown’s work on the subject

- Structured Design by Ed Yourdon and Larry Constantine, 1975

- On the Criteria To Be Used in Decomposing Systems into Modules by David Parnas, 1972

- Numerous discussions with colleagues at work

- My own design experiments as a result

Its still a work in progress, so consider this a first draft that I feel comfortable sharing to get some feedback on.

Designing cohesive modules themselves is out of scope for this article but its a core requirement to be able to apply this model properly. There are techniques like event storming and bounded context mapping that can help identify the module boundaries, and I have talked about them to some extent here and here. Studying the Structured Design book and Parnas’ paper, is highly recommended to understand the nuances of coupling and cohesion.

Definitions

Module

Fashioning my definition after Yourdon’s of a module:

- It has a definite start and end

- Its responsible for doing one clearly defined thing i.e. its self-contained

- It has a well defined protocol of communication with other modules (aka interface). He doesn’t say this explicitly but the chapters on coupling essentially arrive at the same conclusion, hence the topic of this post

Going by this definition, modularity can exist at multiple levels: functions, classes, libraries, services, systems, teams, organisational departments.

A highly cohesive module ideally is likely to:

- Be more composable i.e. lower temporal coupling, wrt other modules.

- Be reusable across various problem contexts (this is a nice to have, not a pre-condition. Use before reuse)

- Have a lower degree of co-change wrt other modules (i.e. more loosely coupled)

Published Interfaces

This is what allows modules to talk to each other.

Published Interfaces are simply C# interfaces and types that are explicitly designed to be exposed to and consumed by, other modules. They are separate from other interfaces and types that might exist in a module.

These published interfaces include C# interfaces, commands, queries, events, and don’t have any other external dependencies aside from what’s needed from the .NET framework, and are defined in a class library project of their own within the module folder with the naming convention: <ModuleName>.PublishedInterfaces.

Inter-Module Communication

A module can only invoke an API on another module if its defined in these published interfaces, not otherwise, even if that another module has that API defined internally somewhere and even if its marked public. It is presumed to be meant for module-internal use only and thus off-limits for direct access until published. Think of this conceptually as the difference between public and private functions in a class.

Practically this means, a module project is only allowed to add a project reference to the PublishedInterfaces project and nothing else from another module no matter how tempting. The system’s DI container will provide an instance of the interface’s implementation at runtime to invoke module behaviour.

The goal with this is to have enough flexibility in the architecture to split out separate services along these published interfaces “seam” without requiring heavy engineering effort. Another way to think of this is “module clients”. If like me you have worked on WCF services before, then the idea of a service client is pretty close to it in spirit.

So the communication works out in two ways:

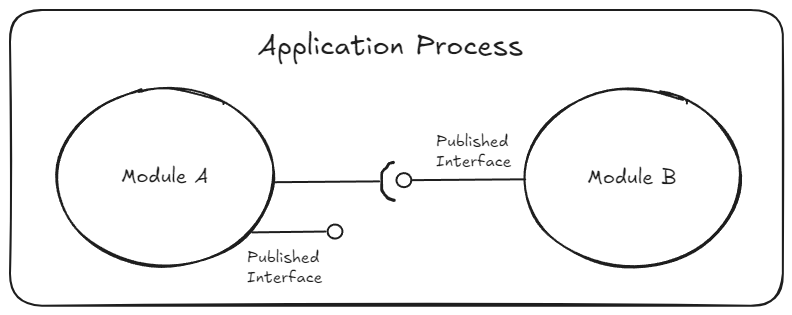

In-Process Communication

Whilst the module is a part of the monolith i.e. in-process and in the same repo, the inter-module communication is in-memory. This is just like a function being called on a class/interface with practically zero transmission costs because all modules share the same process address space, are deployed altogether, scaled together and they die altogether.

Remote Communication

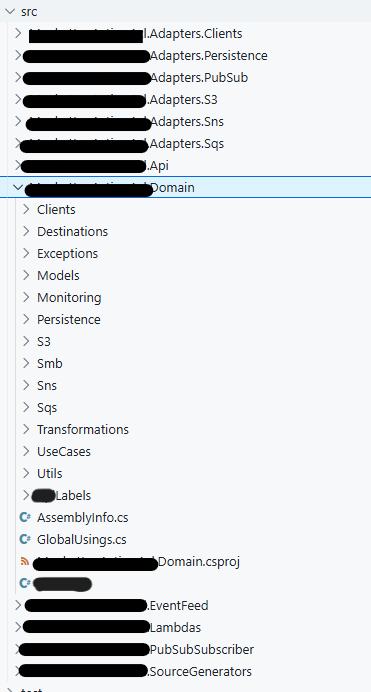

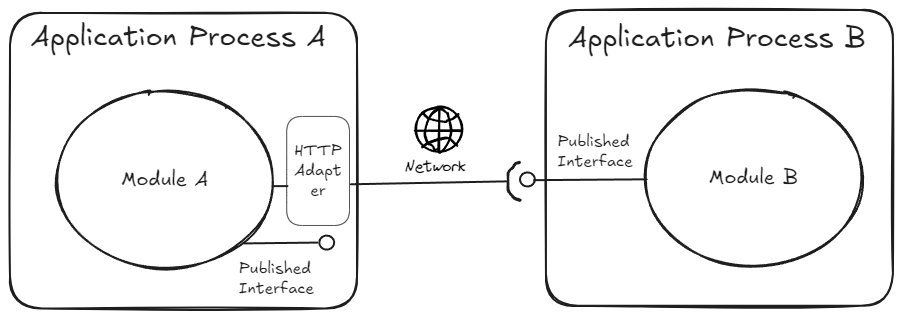

When and if the time comes to split a module out as a separate service (e.g. a web api), then the consumer module only needs to write a networked implementation (aka an adapter) for the remote module’s published interfaces.

Better yet, each module can expose a networked implementation of its own published interfaces via Nuget (aka client package) which makes it extremely easy and cheap for consumers to switch to the remote implementation. The package can bake-in auth, retries, timeouts, correct invocation patterns, bootstrapping hooks etc that can reduce the cognitive load on the consumer significantly who only has to register the client via bootstrapping hooks and start using the client in their code.

Proposed Solution Structure

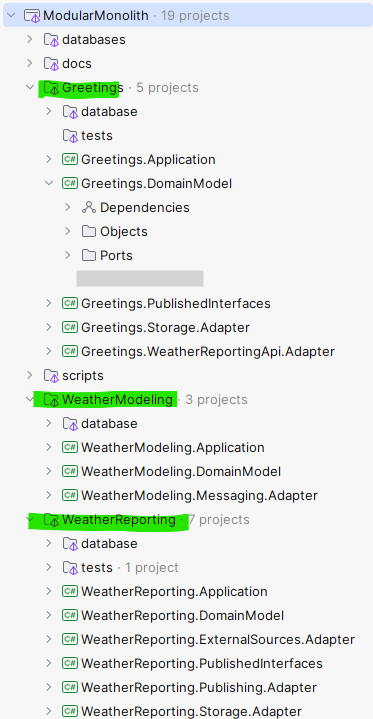

Therefore the solution structure I propose under this model looks as follows:

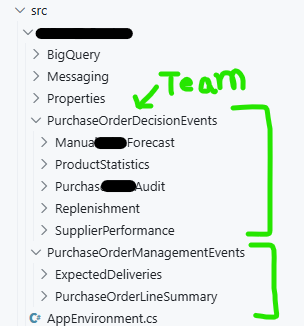

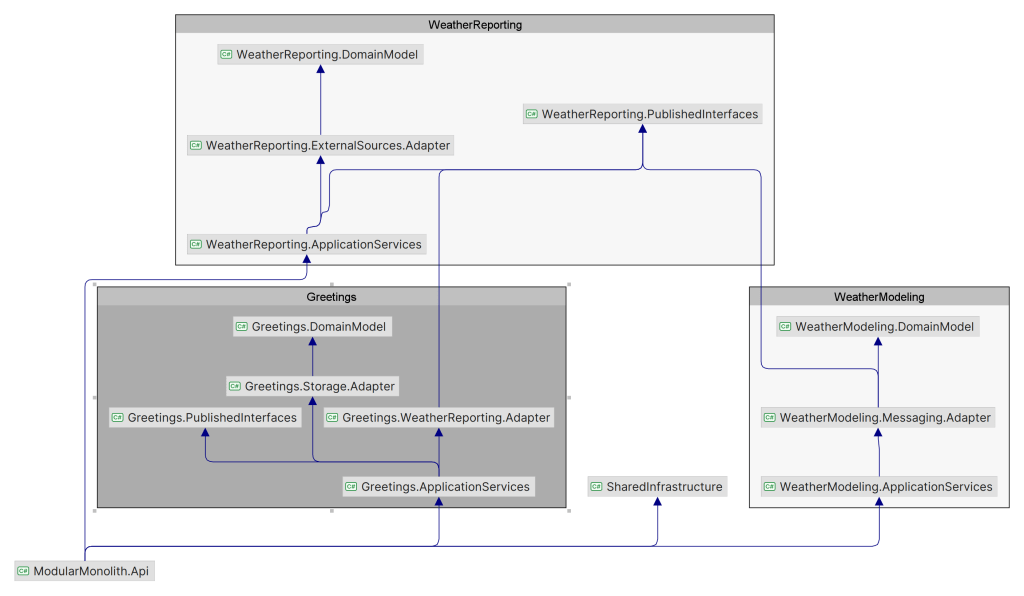

The screenshot shows a proof-of-concept system comprising of 3 modules contained in top level folders (Greetings, WeatherReporting, WeatherModeling highlighted in green).

Rationale for this is when I open a codebase, the folders I want to see first are the business capabilities that that system supports aka purposes of the system, not low level technical puzzle pieces like “Repositories”, “Oracle”, “Pub/Sub”, “Entities” etc. Therefore, each top level folder maps to a single cohesive module (i.e. the business capability or bounded context), but a module’s internal structure could be based on any architectural style – n-tier, Ports and Adapters etc. I am using Ports and Adapters in the proof-of-concept above.

A module defines the following components at a minimum though more are likely:

| Component | Responsibility |

| Domain model | Encodes the solution space model of the domain. Contains aggregates (entities, value objects), domain events, read models, port interfaces, domain services as required |

| Application services | Provides implementations for published interfaces and a bootstrapping hook that the composition root (i.e. the executable application) can call to plug the module in |

| Published interfaces | As mentioned earlier, provide interfaces and types designed for cross-module communication. This is the only project that can be referenced directly across modules. |

| Infrastructure | For any infrastructure that the module depends on e.g. databases, queues, topics, file systems, other modules etc. In ports and adapters parlance, this is where the adapters will go, and adapters are structured around the purpose not necessarily around technologies. |

| Tests | Provides tests for all the behaviours supported by the module |

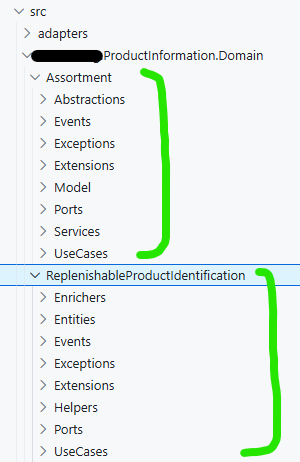

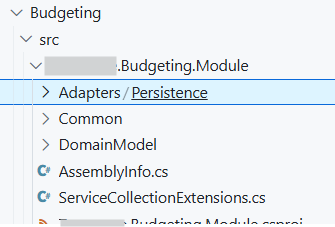

These components can be put into projects of their own (as shown in the screenshot above) or all co-located in a single project separated by folders, depending on the complexity of the module, as shown in screenshot below:

I personally recommend separate projects because that makes enforcing boundaries a bit easier, an internal type or interface in a project is only accessible within that project whereas in the co-located option, its free-for-all.

If I have said this before, I will say it again, all of a module’s components by default are only meant to be consumed within the module and some parts within the composition root that the module plugs-into. No other module in the solution is allowed to “just” add a reference to any project in another module and use its functionality! The only allowed cross-module dependency should be on published interfaces project.

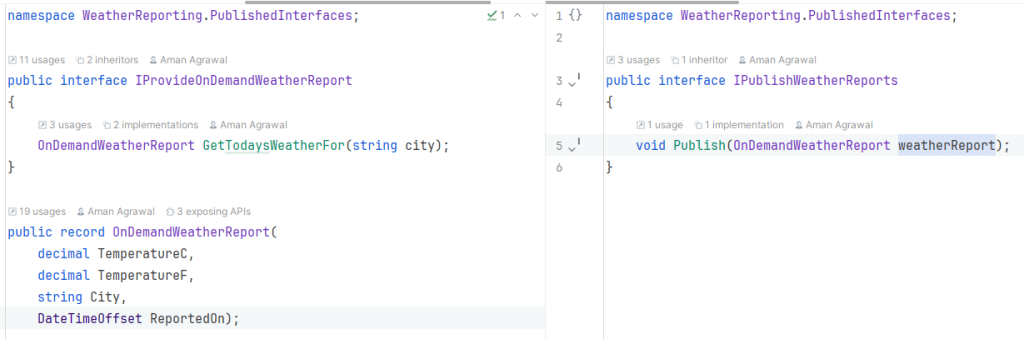

Below is an example of what these published interfaces look like for the Weather Reporting module:

If a module’s functionality is not necessary to be exposed to other modules, it doesn’t have to publish interfaces, e.g. the Weather Modeling module doesn’t publish any interfaces. Its output, likely an updated weather model, is only consumed internally. Interfaces can always be published when needed, but its always a good idea to think about consumption requirements from the outset.

Visualised the module dependencies look like this:

and module internals can be changed without affecting the published interfaces

Enforcing Module Boundaries

With all the modules being in-process i.e. part of the same repo, despite best efforts it can be deeply tempting to take what I call “promiscuous” dependencies on module internals. The anti-dote to that is architecture tests that fail when violations occur.

So we need to enforce the dependency rules quite strictly. Here’s my current specification I wrote for Claude Agent to have it generate the first cut of the architecture tests using ArchUnitNet – a library that allows defining dependency rules using a fluent API and validating them against the architecture of the system. If violations are detected, the tests will fail and prevent the violations reaching production.

Good to know: violations are only detected when a type from the illegally referenced project is actually used in code, non-use doesn't count as a violation.

Some other ways to enforce these rules and get fast feedback:

- Mark all module-internal interfaces as

internalorprivate. But then you will have to expose internals for tests and overtime keep a track of it all can become a burden. Also it can be confusing to see a behavioural interface markedinternal. In general I prefer to mark only those interfaces/objectsinternalthat are implementation details arising from refactoring and do not impact observable behaviour. - Use custom MSBuild targets to define the rules in MSBuild XML and try to catch violations at compile time than at test time. But reading and maintaining XMLs for humans is…😩

- Perhaps some other mechanism that taps into the “add reference” APIs of the .NET project system and stops it from adding dodgy references. Kinda how circular dependencies are prevented. I have not explored this option further, but sounds like it should be possible.

Concerns and Mitigations

The one risk with architectural tests is that people can accidentally comment them out and forget about it or they simply won’t be written because they can be verbose and often repetitive to write. Though this can be caught at pair-programming time or code-review time, the possibility can be still be self-defeating.

One approach to counter this is to auto-generate architecture tests using C# Source Generators. There is only a handful of modularity rules (see spec) that need to be enforced the same way no matter what system it is, so they can be a good candidate for automation. I am not saying that every engineer now needs to write source generators. Writing them and well can be quite cumbersome in its own right, not an effort you want to duplicate across the org. Instead, the source generators could be written/generated by someone in the org once and made available as a Nuget package on the internal package feed (assuming there is one).

The solution structure is another thing you don’t want to have to create manually every single time, so this could also be scripted up. Then its just a matter of running the scripts to create a skeleton structure that comes pre-configured with architecture tests that enforce module boundaries from the get go. I envision this flow to look something like this:

- Engineer runs a script to create a skeleton modular monolith solution providing the names of the modules they want to create

- The script generates the requisite solution structure with all the projects, and also installs the ArchUnitNet and source generator packages into a dedicated architecture test project accordingly

- Engineer builds the solution

- Source generator spits out the architecture tests that can be run to check for violations

- When a new module is added, the source generator automatically updates the tests to cover the new module with the enforcement rules.

- Any changes made to the generated tests will be undone at next build, so dependency rules remain tamper proof.

Fun fact: I used my first cut of architecture tests as a baseline to have Claude Agent generate a source generator that can generate architecture tests from a list of modules. AI 1 - Human 100! 😂

Limitations and Other Thoughts

I have not tried things like gRPC or GraphQL and how presence of these technologies will influence this model. I suspect it won’t be too different, because ultimately all these represent networked implementations of published interfaces. May be I can extend the PoC to play with these as well.

I am also adding asynchronous scenarios with message brokers like Kafka or queuing systems like SQS, so I can see how this model works when the inter-module communication is asynchronous. With Kafka ecosystem having contract enforcing tools like Schema Registry, it could be an interesting exploration.

Architecture tests using ArchUnitNet require assembly loading to verify dependencies, and that requires access to a public type in each assembly. Because my architecture tests are generated dynamically, for now I have worked around this by creating a DoNotDelete.cs class in every non-test project that the architecture tests can just hardcode i.e. “convention over configuration” to load assemblies. But if that DoNotDelete.cs gets well…deleted…architecture tests will stop working. It would be best if assembly loading wasn’t tied to a public type but rather the namespace or folder location or something. Its possible that other architecture testing libraries support that, so I am going to have to explore that.

Since source generators cannot inspect assemblies other than the one they are installed in, currently to generate architecture tests for all projects I am having to define a custom MSBuild target in the architecture test project that spits out the namespace of all projects in a text file. This text file can then be read by the source generator as AdditionalTextFiles to pull the list of modules. If there is a better way to scan all projects in the solution, I am all ears!

The direct implementation of published interfaces is protocol agnostic, however, if a module needs to expose those APIs over HTTP, then it has two options in ASP.NET Core: minimal APIs or explicit controllers. The PoC only shows the former but I don’t expect controllers to be particularly difficult given that ASP.NET Core can resolve controllers from any assembly. What’s worth bearing in mind that the web API MUST at least expose HTTP endpoints for the Published Interfaces, but it can also expose more endpoints that are not a part of Published Interfaces. These “extra” endpoints I’d consider as internal to the module i.e. invoked only by the frontend application of the system, if any, or for some control plane operations, not other modules.

Published Interfaces model essentially is about separating internal and external behaviour of a module just like separating public members from private members in a class. This affords some flexibility for the engineering team to evolve the internal design of a module without negatively impacting the published contracts. Any change to published contracts needs to honour the same etiquette that one would whilst changing a public API anywhere – pro-active communication, versioning, preserve backwards compatibility, provide consumers a safe and flexible migration path, monitoring.

An interesting variation could be further classifying Published Interfaces as domain internal (to be consumed by modules related to the same business domain)and domain external (to be consumed by modules outside the business domain). This can allow greater flexibility, clarity and control for slightly higher maintenance costs, though I would argue having internal and external concerns mixed in one interface has more overhead. Something worth exploring!

Anyway, I have created a proof-of-concept repo that demonstrates this model in a lot more practical detail over at Github with all the scripts, architecture tests, dockerisations, database treatment etc. I’d be keen to know what do you think of this Published Interfaces model? Does it make sense? Did I miss anything? What else could I try?