In this final part (checkout part 1 here) I will share my experiences with custom instructions and custom prompts for refactoring and bug fixing. I applied these techniques on backend C# code at work across different repositories that represent a varied cross section of domain complexity.

I started by crafting the following:

- copilot-instructions.md (here I wrote general context about the repository, where is the code, where are the tests, what libraries and frameworks we’re using, what’s the application architecture style in place etc. just to prime Copilot with the general constraints of the codebase)

- refactoring-rules.prompt.md (here I wrote refactoring specific rules. I want to enforce TDD based flow so that’s what’s encoded in here. I will put in this prompt anytime I want Copilot to refactor some code)

- bug-fixing-rules.prompt.md (as you can imagine, this contains the rules of bug fixing. Fairly similar to the refactoring ones because…TDD…but with a bug fixing focus. Needless to say, I will put in this prompt for bug fixing work)

With these in place, I started with my experiments:

Refactoring

Prompt Given

There are following problems in this file:

Executemethod is too long- It has multiple nested loops

- It uses

#regionto separate functional code blocks- Most of the domain logic is scattered throughout the method instead of being defined in the low level domain objects ({inserted a list of object names for additional context})

- The use case file defines lots of internal types that may or may not be necessary

Refactor this code to improve its:

- separation of concerns

- modularity

- cohesion

- coupling

Observations

- It ran all the tests 3 times before changing a single character of code 😆 (better than not at all in the first experiment. Might need some tweaking of the custom instructions)

- It then ran off and made a bunch of refactoring changes instead of making one small change at a time and validating them with tests (ok sometimes my own surface area of refactoring is larger than it should be as well, because I know tests have got my back, so acceptable).

- Ran the tests, they failed.

- Instead of reverting the changes, it carried on making changes in a bid to pass the tests (I personally prefer to revert and try again because it allows me to fine tune my thinking).

- Steps 2-5 repeated 4 times and on the 4th attempt, all tests passed! 🎉

- Reviewing the refactored code

- Use case got approximately 50% shorter

- At a top level, the flow read a lot better than it did before

- It moved some logic to the low level domain objects but it kept some of the local types which I don’t believe were necessary. This will need some manual tweaks to get into shape.

- Lot of the data slicing and dicing operations were scattered into fragmented LINQ operations in different places, it combined them all together into logically cohesive LINQ operations encapsulated into functions, which reduced noise quite a bit.

- Also, modifying the input collection? Yikes!😬. Immutability?

Comparing With My Earlier Manual Refactoring

- Largely similar except I didn’t cohesive-ise LINQ too much and I created more internal modules to coordinate the processing

- Low level domain logic was more complex in AI generated refactoring than mine (nearly 2x as much code written by Copilot as the manually refactored version, to achieve the same effect. More loops, more conditionals etc, will require additional refactoring to simplify.)

- I managed to eliminate most explicit types in favour of localised anonymous types because they don’t really have any meaning in the domain, they are mostly convenience data pivots. Agentic refactoring eliminated some types but left some others in. Not a huge difference, though I prefer my version.

- However, both versions mutate the input collection! Yikes x 2! 😬. Bad form on my part! I would at least try to make it immutable before merging into the main branch.

Conclusion

Not too bad overall and much better than the first attempt I wrote about in my first post! Custom prompts instructions do seem to constrain and guide Copilot a lot better. I would still make incremental commits after each round of successful refactoring, reduces the amount of rework if Copilot starts hallucinating.

Will I use LLM assisted refactoring going forward though? I have a modestly decent refactoring practice, plus for me refactoring is an exercise in learning and exploration of design ideas and I don’t want additional hops between my brain, my hands and the code. Adding LLM to that flow just creates a rather large disconnect between my ideas and the outcome. Trying to understand its refactoring rationale and the outcome of that rationale to me seems quite a cognitively expensive activity.

If I don’t know the code myself it will be very hard for me to assess if the agentic refactoring makes sense, even if I have constrained its flow with custom rules/prompts. If I know the code well enough, then I can experiment with refactoring ideas myself or with another human pairing partner, so I don’t really need an LLM in that flow.

I don’t imagine I will be pulling a completely unfamiliar repo, running LLM on it to refactor it left and right without first understanding what I am refactoring and why I am doing it, anytime soon.

Fixing Bugs

For this experiment I used a recommendation system codebase that has a fairly complex rule engine.

Setup

- Pick any rule and alter the code (i.e. inject a bug) in the smallest way possible at the lowest level of module hierarchy.

- Hopefully at most one test should fail, meaning the bug is valid

- Remove the failing test(s). I want to see if Copilot can write those tests correctly

Bug Injection Examples

The following might be a good if not a complete set of examples of subtle bugs that can creep into the system. Thus, might be a perfect experiment for AI tools:

- Changing a

<to>or (>to>=) etc - Changing a number slightly (e.g. make a

3and8or make a6a9) - Swap around the same typed arguments in a function call (e.g.

Process(int a, int b)) - Alter string literals

- Omit certain headers from an outgoing HTTP request

- Disable idempotency checks

- Remove null reference checks

- Throw an exception abruptly in the middle of the code

- Flip a

falseto atrueor vice versa

I tried two of these variants: changing a number and flipping a boolean

Bug 1 : Change a number

First prompt:

A user has reported a bug in

Rule1, that it says no recommendation is needed instead of evaluating next rule. Following thebug-fixing-rulesattached, fix the bug.

Observations

- It followed the bug-fixing-rules…somewhat

- However, instead of writing a new test, it got satisfied with the fact that there were tests that were targeting the rule regardless of whether or not those are the right tests for the bug in question.

- Instead of fixing the actual bug introduced, it made an unrelated code change i.e. inverted an in

ifconditional for no benefit - Ran the tests which passed (because they weren’t targeting the bug), so pointless.

- Declared success! 🤦♂️

Improved prompt (aka spill the beans):

A user has reported a bug in the

Rule1, that, it says no recommendation is needed instead of evaluating next rule, perhaps something to do with how dates are compared. Following the bug-fixing-rules attached, fix the bug.

Observations

- It followed the bug fixing rules, this time properly

- This time it wrote a new test to prove the bug because it noticed that the logic is testing for “6 days either side of today” yet the numbers in the boolean condition don’t match up with that expectation, 6 and -8 instead of 6 and -6. Bravo!👏

- The new test failed as one’d expect

- It fixed the -8 to -6, reran the tests and this time the tests passed 🎉

- I also think that good naming in code might help Copilot make sense of things. For example in this case the function name has

...SixDaysEitherSideOfTodayin it and it spotted the inconsistency in the actual logic. If names were bad, it might struggle a lot more, might be something to try. - Notice I also provided it with the actual file where I had injected the bug

Bug 2 : Flip a boolean

Prompt:

Customers have reported a bug that notifications are being published, yet, the data is not updated successfully. Following the attached rules, fix the bug.

I also added all the relevant files into its context window and a couple of context tools: Find Test Files, Test Failures

Observations

- It identified the root cause pretty quickly, “the bug seems to be in class A where the method X is returning

trueeven when there is data conflict detected” 🤯 - However, it made changes in all the wrong places to fix the bug. It wrote tests at the wrong level of granularity (caller instead of the callee). It mocked the system under test.🤦♂️

- Of the 9 attempts to get it to do the right thing, only 3 attempts panned out. That’s a reliability rate of around 30% 😟

- However, in all those 3 attempts, I noticed I had the culprit file open and in focus in my VSCode editor and all the other attempts had a different file in focus. So I tried this bug a couple more times, to see if there is something to this observation, and there was. It fixed the bug correctly everytime I kept the culprit file in focus in the editor and utterly failed when the file was open but another file was in focus. It went down all sorts of rabbit holes and produced different results each time.

- Bottomline, I needed to do my analysis of the bugs first and narrow it down to the suspect files and make sure all those files are included along with the context of the bug and my suspicion of where the bug might be. Just like I’d expect users to give me context and expectations around bug so I can address it properly, I have to make sure Copilot has all the context as well. It has no sense of where the bugs might be if I give it an open ended prompt like, “fix a bug in this file”.

Bug 3 : Something from the backlog

Too ambitious! 😀

Observations

- Bug stories in JIRA often have vague and sometimes incomplete context (mainly because they rely on implicit context that engineers experienced in the domain already have)

- Most if not all these bugs are reported from a user’s perspective which is the tip of the iceberg. The bug might be visible in the UI or in some report somewhere but the actual underlying cause might be anywhere in the complex web of backend service interactions which you will need to narrow down to the culprit service(s) first.

- This means I cannot simply dump the story details into Copilot and set it loose fixing the bug on its own. It wouldn’t know where to start, but it will definitely fix something!

Conclusions

Even though I injected bugs myself, I still had to make sure that the suspect files were added to its context windows. Expecting LLMs to figure out where the bug is and then fix it all with minimal prompting and context, is unlikely to work . If this were a real life bug, then I would have to do the analysis to find where the bug likely is and then I can get LLM involved in the fixing part.

Could LLMs be used in the analysis part to figure out where the bug is? Possibly, if the bug report had enough context and there was a repeatable and standardisable way of mapping it to parts of the system architecture, that could be fed to an LLM that could then help narrow down the bug hunt. Thing is problem solving depends on the problem complexity, domain context and skill level of the solver, its hard to create a template for this kinda stuff that agentic tools can just execute and replicate human behaviour (regardless of what marketing says).

May be the bug fixing rules could be enhanced to reduce hallucinations further, certainly adding tools like test failure results, terminal output etc increases the quality of diagnoses and subsequent corrective actions.

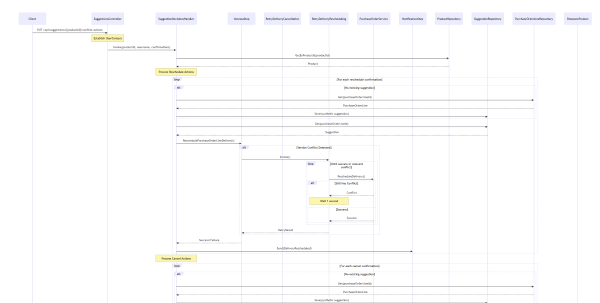

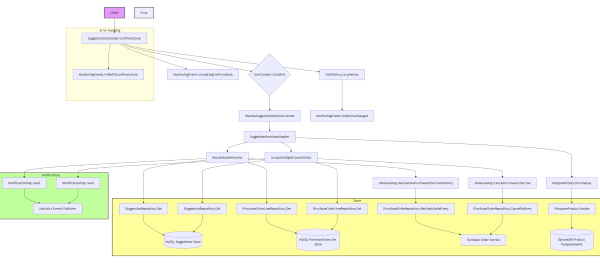

Bonus: Generating Flow Diagrams

Since I still had a few Copilot credits left, I figured I would try something that I genuinely think can be a big time drain on engineers – visualising dependencies/flows from ever changing code.

Often times, I find myself having to visualise some complex backend flow in order to participate in architectural discussions or create a design improvement proposal or to just update my mental model of the current design. I typically do this from code because any early diagrams might have gotten out of sync with reality, so I painstakingly follow the call graph one function at a time and create a sequence diagram or a flow chart in Lucidchart or something. Visualising flows like this helps reduce noise for me and helps me get an overall sense of the design.

I know there are other tools that I can use to do this or write some tools myself, but if I can have LLMs generate it based on natural language prompts, that’s a better use of my time because drawing diagrams is undifferentiated heavy lifting. I am often interested in the outcome, not how I got to it. This is obviously different from writing code that I want to be able to understand and change.

So I told it, “Generate a full sequence flow diagram for the Process method in the Foo class, don’t skip anything, also include the baz and bar classes into the flow. Generate a mermaid formatted output for the diagram, put the diagram in docs folder and commit the file to git.”

The results were very good, not perfect, but very good! All diagrams were correct and perfectly readable, some times it would skip some dependencies but upon asking it to include them explicitly, it would comply. It also colour coded various sections of the flow which helped with reading the diagrams.

Closing Thoughts

With custom instructions and specification techniques, you can certainly get to a better outcome with agentic tools/vibe coding, than without them.

Is it really worth the time and effort to write these down to some non-trivial detail so LLM tools can do a better job but only up to a point? I don’t know! Its hopefully a one time thing so may be the long term ROI of this effort is not too bad, but what problems are we really solving with these tools? Would I still learn these techniques and use these tools where they make sense? Sure! Its just another skill to learn and tool to use to support my work, I am not going to reject it out of hand without learning and using it, how else am I going to know where it works well and where does it fall over?

We often say automate the boring, mundane, undifferentiated heavy lifting that drains human productivity, which is right, but don’t club learning and improvement activities into that pile. Bug fixing, refactoring, new features etc are all learning and improvement oriented activities, the more we learn, the better we do, more productive we get over time. They are the opposite of undifferentiated heavy lifting if you are building and supporting non-trivial products that add value to your customers.

Where does productivity drain come from in software engineering at companies? Here’s parade of shame:

- Hunting for information/documentation from multiple sources for the same thing for the n-th time

- Filling out useless forms

- Context switching (and excessive cognitive load)

- Attending long draggy meetings (Agile circus)

- Hand rolling standardisable infrastructure and platform (or any code that you write almost the exact same way every time)

- Working on the wrong problems

- Doing manual deployments and testing

- Centralised manual approval gates for design and architecture

- PR reviews

- Unavailability or inaccessibility of domain experts

- Bad org culture and politics (with “IT in the basement” syndrome)

I would love to have AI solve all of these but its unlikely because we haven’t solved these yet! 🙂