I have been reading & hearing a lot about how AI/vibe coding will make software engineers obsolete and that agentic coding is like magic, you can just give it a prompt, kick back and doom scroll social media whilst the AI minions carry out your bidding completely autonomously making one engineer worth 10. Some of these folks exhibit a very strong Dunning-Kruger effect, some are just selling AI products and some have millions invested in AI companies so they need to protect their investments.

Either way, I think its important to form your own opinion so I decided to give agentic refactoring a shot to see where it works, where it faulters, is it really worth the hype, what might be some of the ways to work with these tools effectively. If you just want my formative heuristics and/or conclusions without reading how I got to them, knock yourself out!

Disclaimer 1: I have only tried agentic refactoring for a couple of days so this article is in no way exhaustive or super scientific. Though I have been using AI tools to write code on and off for a while, mostly for experimentation purposes.

Disclaimer 2: Its possible that my prompt engineering skills are not quite there yet and I need some variation practice to fine tune it.

The code I tried this experiment on however, is real life production C# code from work so its not one of those toy problems like Fibonacci or fiz-buzz. Matter of fact, I used different repositories of varying complexity to try out different refactoring scenarios. In the end my goal is to see if I can create some sort of heuristics for realistic agentic refactoring, if not outright reject it from my workflow. I used VSCode’s Copilot in Agent mode using GPT-4o and Claude 3.5 Sonnet models (I had better results with Claude). I have also been experimenting with Rider’s inbuilt AI Chat in Edit mode with Claude 3.7 but the results are often similar for these scenarios. Also to make it clear, changes made in this experiment are not destined for production.

Scenario 1 Refactoring an Existing Use Case in a Purchase Ordering Backend Service

This is a fairly complex use case (multiple conditional flows, state mutations, domain events being captured, transactional control etc), with some deprecated code living side by side to new code as we are migrating from old architecture to new.

I asked Copilot, “Refactor this code! Ignore the obsolete warnings, they are known but refactor everything else”. Fairly open ended prompt but only because I wanted to see how it would perform, I can imagine an enthusiastic junior engineer giddy with the prospect of being very productive without the cognitive “overhead” of thinking, might input a prompt like that. Not totally impossible.

Observations

- ❌First refactor broke the code because for some reason it decided to define the

purchaseOrderIdparameter in one of the methods as aGuidtype whereas it should have beenPurchaseOrderIdvalue object type. It wasn’t able to infer the pattern from the code. - ❌When asked to fix this type error, it also changed the obsolete code which I specifically asked it not to touch. Not only that, it fixed the type conversion problems, but added a bunch of new replacement types for the ones marked

Obsoletedespite me asking it to not touch deprecated code, it somehow decided that new implementations were needed even though they weren’t necessary. - ⚠️When I asked it to undo what it did, it emptied out the types but left the empty files in the repo. I had to make another pass to delete files manually (though this could be because Copilot is not allowed to directly delete files on my machine or run scripts without my consent)

- ❌It unnecessarily changed the name of one of the async methods to add the

...Asyncsuffix to its name, even though in this repository we don’t follow that pattern. This unnecessary change rippled out to multiple places. - ⚠️Overall, after about 30 minutes, I was completely lost as to where the code stood at that point and I had to basically do a

git reset --hardand start over again. And, I know that codebase and architecture fairly well, imagine a new team member unfamiliar with the code taking on the task to refactor it with the help of LLMs, its not hard to see how this could result in a net productivity loss (for the engineer and the organisation).

Scenario 2 Same Code, But Ask for Refactoring Recommendations Instead

I thought ok, what if I changed tactic and instead of asking Copilot to basically blanket bomb the code, ask it for refactoring recommendations. So I asked (in a new chat so it’s context is not poisoned from the previous one), “What suggestions for refactoring do you have for this file?”

Observations

- ✅⚠️It suggested a rather long list of refactorings (11 or so with reasons and examples), I rejected a whole bunch of them since they didn’t add much design value e.g. pulling out one liner private functions is just over-modularising code at the cost of readability and locality of context. If the code all relates to the same logical concept, I’d rather keep it all in one or fewer methods than break it up into too many small methods. Modularity is about abstracting complexity, there needs to be some! However, the following recommendations seemed sensible:

- Simplify LINQ

- Reduce nesting in loops

- Consider using strategy pattern

- Extract smaller methods

- Add additional unit tests

- ✅Of these sensible ones, I asked Copilot to narrow them down to the 2 most critical refactorings it would do and also explain why. It narrowed them down to the following with good enough reasoning (sadly, I couldn’t find a way in VSCode to save chat transcripts in a human readable format, so I can’t show its response verbatim. You’ll just have to trust me that it wasn’t bad):

- Strategy pattern implementation (because there was conditional logic for each of the 3 business functions that the domain objects supported)

Before code (pseudocode):This file contains hidden or bidirectional Unicode text that may be interpreted or compiled differently than what appears below. To review, open the file in an editor that reveals hidden Unicode characters. Learn more about bidirectional Unicode charactersDoFunction1(...); DoFunction2(...); DoFunction3(...); // impls DoFunction1(...) { if (condition A is true) DoThingA1(...) else DoThingB1(...) } DoFunction2(...) { if (condition A is true) DoThingA2(...) else DoThingB2(...) }

Copilot’s recommendation (pseudocode):This file contains hidden or bidirectional Unicode text that may be interpreted or compiled differently than what appears below. To review, open the file in an editor that reveals hidden Unicode characters. Learn more about bidirectional Unicode charactersStrategy1 { void Execute() { if (condition A is true) DoThingA1(...) else DoThingB1(...) } } Strategy2 { void Execute() { if (condition A is true) DoThingA2(...) else DoThingB2(...) } } //usage var strategies = [new Strategy1(), new Strategy2()] foreach (var strategy in strategies) { strategy.Execute(...) } - Extract smaller methods (because the entry point code had code related to transaction scope control, idempotency check, publishing events etc)

- Strategy pattern implementation (because there was conditional logic for each of the 3 business functions that the domain objects supported)

- ✅💭First off, I liked the fact that it was able to distill out a real design pattern based on the code it “saw” in the file. However, was the pattern actually needed? There is no way Copilot knows that, I as a human engineer on the other hand, do. Knowing the domain and the system as I do, its clear to me that we are only likely to have those 3 kinds of functions, adding strategy pattern in the anticipation that we’d have enough functions to warrant it, is over-engineering. Besides, implementing this pattern is not all that difficult and we have good tests, so I can add this pattern when a need presents itself.

This also gives us more time to create a better abstraction/API for the abstraction based on better understanding. Adding it upfront is not the only way to enable future change, deferring abstractions/patterns is also a perfectly valid way to do so. So I rejected this suggestion of Copilot’s, though its plausible enough for me to keep in my pocket!

- ✅Extraction of smaller methods from the entry point function was perfectly acceptable refactoring because it pushes details down the call tree (aka deep modules) and allows the entry point to just be a delegator. So I accepted this refactoring, ran my tests and committed the code.

- ❌As a bonus I asked it to add some missing tests that it had mentioned in the list of refactorings, this was a mistake because things went pear shaped. It added a new test file even though there were already tests for the use case so extending that test suite would have been more sensible. But even then, the new tests didn’t provide additional cover, we already had tests for that flow. Not sure how it didn’t spot that! I reverted this change 🤷♂️.

- ✅What was nice was that I was able to refer to the refactoring in the list by its ordinal number and Copilot was able to look it up correctly to have a conversation about it. This saves having to type longer descriptions, “implement the extract method refactoring but not the one with…but with…”. Instead I just said, “implement number 3” and away it went!

Scenario 3 Moving Logging Code into Extension Methods

A quick org tech context first, we use a convenience composite class that wraps Serilog’s ILogger interface and the Metrics base class from DogstatsD, for sending logs and metrics to Datadog. This allows us access to both the logger and metrics APIs from one place without having to inject the same 2 dependencies everywhere:

MonitoringHelper.Logger.Warn(...) or MonitoringHelper.Metrics.IncrementCounter(...)

However, if the logging is a bit more complex, then this chaining becomes quite verbose and annoying to read well. So we tend to move this monitoring code into appropriately named extension methods like MonitoringHelper.LogCallFailed(...) and declutter the client code a bit.

So, for this scenario I targeted a very simple class, all it does is spin up a background task which executes a lambda and the lambda has some logging in it. No more than 20 lines of code, something similar to this:

| Task.Factory.StartNew(async () => | |

| { | |

| try | |

| { | |

| // | |

| //do some processing here | |

| // | |

| MonitoringHelper.Logger.Information(....) | |

| } | |

| catch (Exception exception) | |

| { | |

| MonitoringHelper.Logger.Error(exception, ....) | |

| } | |

| }, cancellationToken); |

I asked Copilot, “move the logging code into an extension method defined on MonitoringHelper type, in a separate internal static class in the same file”

Observations

- ✅It correctly created the extension method and class and renamed it on demand as well

- ❌When asked to move the extension class to a separate file, instead of opting for the closest namespace (which is the one where the

TaskSpinnerclass lives), it added this class to an already existing extension class, so not even adding the extension method to the existing class but tacking it on as a separate class. 🤔 - ❌When asked to move it to the right namespace, it merely copied it over leaving the previous one dangling and this immediately caused a conflict because now there are two occurrences of the same class in the same namespace.

- ❌⚠️When asked to remove the duplicated extension class it merely moved the method into the existing class (which is what it should have done in the first place!?) 🤷♂️

- ❌Eventually I had to take over and correct a couple things e.g. it moved the types around but didn’t resolve missing imports and needlessly made types

publicinstead of the most restricted that’s needed. This is the kind of context and sense an experienced engineer thinking about modularity and access will have.

Scenario 4 Restructuring Code Into Modular Namespaces

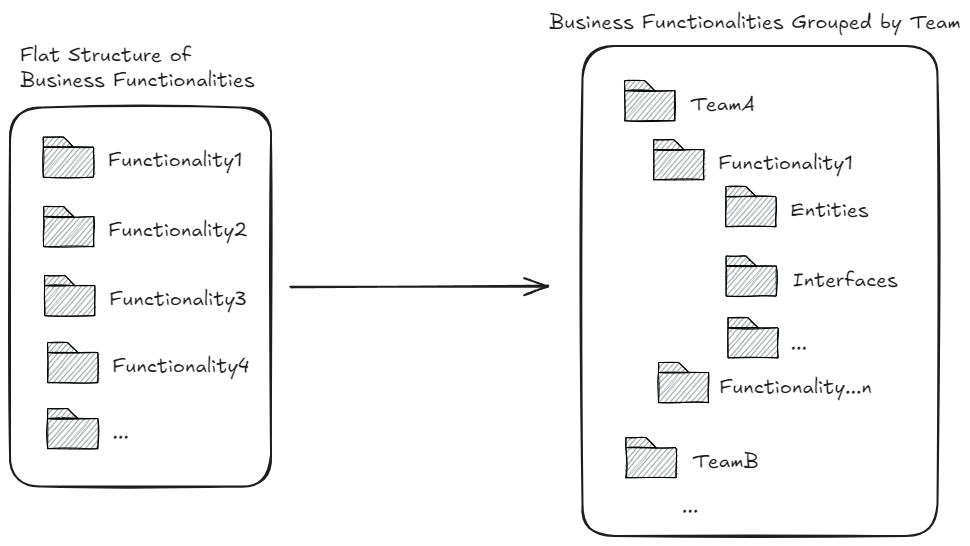

For this scenario, I used a different repository that had files strewn all over the place organised by technical layers: entities, utilities, services etc at the top level. This is a modular monolith where modules are owned by separate teams but the code structure doesn’t make that obvious at all and this can often lead to code duplication (or worse, code misuse across module boundaries)

So I asked Copilot:

“There are 4 folders in MyService.Domain project (Functionality1, Functionality2, Functionality3 and Functionality4) that I want to group into the team specific folders. So create two team specific folders: Team A and TeamB in this project. Then move the following folder and all its content to TeamB: Functionality3.”

Observations

- ✅With incremental instructions, Copilot moved the code around fairly smoothly. No errors or failures. However…

- ❌…I noticed the namespaces in the moved files didn’t reflect the new folder structure🤦♂️. This made the dependency graph look completely off and confusing. Not to mention compiler warnings about mismatched namespace mushroomed everywhere.

So I followed up, “Fix the namespaces of all the moved files to match the folder structure”

Observations

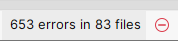

- ❌After about 45 minutes or so of making all sorts of changes, Copilot confidently concluded:

“The folder structure and namespaces now correctly reflect the new organization with TeamA and TeamB as the main folders.”

However, the build failed because it messed up all the dependencies. What happened next is best shown with screenshots from the chat:

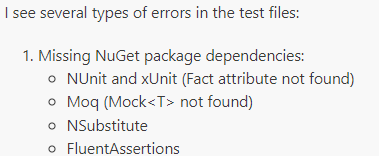

After about 30 more mins of trying to “fix” build errors…

So in all I think I spent around 90 minutes, and I was left with this:

- 💭I decided to throw away all that gunk and just used the old fashioned file move refactoring in Rider that not only moves files but also fixes the namespaces automatically. Result? I was done with the full refactoring in 7 minutes flat with zero build errors and all tests still ✅. Human 1 – AI 0 😆.

Yes, I switched IDEs, cruel me! But, it turns out that’s not a disadvantage for AI because it sucks just as bad in Rider when it comes to moderately large scale structural refactorings. I actually did another exercise using Rider’s AI Chat feature in Edit mode. More or less the same results!

Other Goof Ups + Observations

❌Highlighting some code in the editor and asking Copilot to do some refactoring on it was a comedy of errors. When asked to extract a new method from selected lines, all it did was just replace the selected code with a method name, didn’t actually create the implementation of the method. WTAF? 😀 This is where I noticed some differences between the underlying model used:

- Claude 3.5 Sonnet fared better in this regard, it was able to refactor out a method implementation, in the first attempt!

- Unlike GPT-4o, Claude 3.5 also seems to check the code for compilation failures and fixes them automatically where it can

- However, just like GPT-4o, it also struggles if the code under refactoring is complex i.e. it has conditional logic, long methods with multiple steps or there is obsolete marked code that can’t be removed just yet or there is a slight deviation from the strict DI pattern. Time and time again Copilot got so twisted tripping over itself, it couldn’t see the compilation errors at all and couldn’t get out of it.

💡At least with C# (I don’t know if other frameworks or languages will perform better), Copilot when moving code around doesn’t seem to realise that the new file is missing imports so it never fixes them leaving a broken build. Giving it precise numbered instructions for cases like pulling out an extension class, seems to work well:

- Move the logging calls into an extension method in a seperate class called XyzExtensions.

- Move this new class in the same namespace as the use case.

- Make sure all the required namespaces are imported to avoid build failure

- etc…

Emerging Heuristics

I know this is way too little and too soon to be talking about super meaningful heuristics for agentic refactoring but throughout this exercise there were regular glimpses of oasis in the midst of mostly dry and parched desert. Its not nothing, even if somewhat of a foregone conclusion since I am seeing similar heuristics pop up in other people’s experiences as well:

- Agentic refactoring seemed to do better on small and very focussed tasks (e.g. “Rename this method in this file” or “break this method in this class into smaller methods” or “make sure to add a dependency on this interface and register it in DI container” etc), rather than a blanket, “here’s a big complex codebase, refactor it”. Bottom line, if I can reason about the change in my head easily, AI will be able to as well. If I struggle to reason about the complexity and can’t articulate it to AI well enough, then AI will struggle too and in that case its default is to hallucinate. It cannot do critical thinking on my behalf, it can only predict the next token it just might not be the token I want.

- Human engineer must be in control of the workflow if you want to make meaningful forward progress instead of 1 step forward, 5 steps back. Testing and (committing or reverting) i.e. TCR in small incremental steps after every agentic change is non-negotiable. A way could be to ask AI for all refactoring recommendations upfront and then surgically having it implement only the ones that the human engineer knows (with the benefit of domain experience and context), add design value. Throwing away any junk code and either retrying or taking over at any point should be easy. You will really need to work hard to push against the charm of “more code faster” to do this one well, juniors can be particularly susceptible to it, but given enough time seniors can also fall victim to it!

- If the refactoring is straightforward enough or there are dedicated refactoring tools for it, instructing an agent to do them takes more time than just manually executing the refactoring yourself. For example, removing unused namespaces manually took me a couple of seconds (because I know my keyboard shortcuts), Copilot got completely confused and removed in-use namespaces from completely wrong files, and wasn’t able to fix it. What was supposed to be a couple of seconds, took several minutes and a bunch of daft changes and still wasn’t done.

Agentic TDD

Here’s a flow I’ve seen used in human-human pair programming sessions and I would like to see how it pans out in human-machine pair programming sessions:

- Human engineer figures out what tests they might need to write for the system under development based on the desired behaviour

- Human engineer writes the first/next failing test first with only stub code generated using conventional refactoring tools so that the code at least compiles. If no more tests to be written, go to 5

- Human engineer then asks the agent to fill in the implementation that it thinks will pass the test

- Human engineer runs all the tests to validate the changes

- If all tests pass, then:

- Human engineer commits changes

- Human engineer asks the agent to do specific refactorings if needed or asks the agent to suggest refactorings which the human picks and chooses from for the agent to implement. Go to 4

- If the human decides that no refactoring is necessary at this point, go to 2

- If one or more tests fail, go to 3

- If all tests pass, then:

- Done!

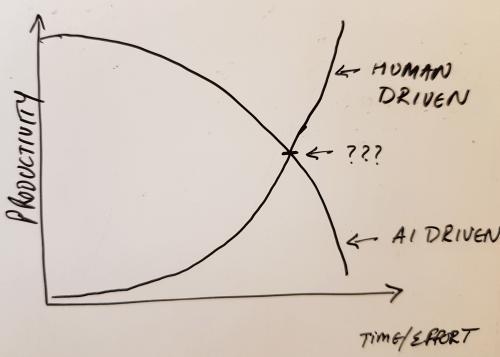

My Conclusion…for Now

The whole experiment was a struggle between being methodical and strategic with changes, and chasing the elusive “10x productivity”. Yes, even an experienced engineer like myself, cannot escape the charm of building/refactoring things…fast! If the measure of productivity is “more code faster” (spoiler: it isn’t!), then humans have already lost by a mile and AI should take our place.

However, seeing the results from my experience with AI assisted coding, refactoring etc, I now have a large pile of instant legacy code (code with no deliberate design, no tests, no documentation, no monitoring), and I have spent inordinate amounts of time on refactorings that just on my own would have taken a lot less work because I know the context and the domain, so where’s my productivity gain? Why am I working so hard to make the machine work a teeny bit better? And are those improvements even permanent or will I need to work just as hard the next time I open a new chat window? Is “typing” really the issue here or is it everything else?🤔

In fact, I would say whatever short-term productivity gains I am supposed to have with AI today, are likely to be nullified when all this rapid fire code needs to change or evolve. The worst part is the rush of “more code faster” is likely to blindside me from paying attention to what is being generated, so whenever I have to change this code, I will be up the creek without a paddle. Now imagine the net long term productivity loss if this scaled out to an organisation of hundreds, thousands or tens of thousands of engineers 😱! Yikes! I am no AI expert, but GitClear’s study from the last couple of years (which is also corroborated by another independent study done by Google which GitClear’s references), might indicate the source of the productivity loss – unstable software systems built with indiscriminate short term speed seeking AI usage – that will require large scale rework to stabilise.

So my view is that all the over the top claims about increased engineer productivity (or engineer obsolescence) are being made by people who know the least bit about software engineering or AI, or are trying to protect their investments in AI startups or are beneficiaries of such investments, and thus should be disregarded outright. That said, with human-in-the-loop and a bit of discipline a happy medium might be struck and we might actually give the next generation of these models better quality code to train on, time will tell.

Anyway, I have ranted enough for now! Here’s some more food for critical thought:

Another Cursor-er

Simon Wardley’s “vibe wrangling” experience

Kent Beck’s vibing experience

Internet eating itself? by Stephen Klein

Products vs programs by Dylan Beattie

Even the consultants are defending their turf 😆

Panic induced AI adoption by John Cutler

Economics of AI by Stephen Klein

Build LLM from Scratch if you want to learn about LLMs under the hood

One Reply to “Some Observations on AI/Agentic Refactoring”