Back in 2021 I had the privilege of attending an Event Storming masterclass in Amsterdam from the man himself – Alberto Brandolini. It was an epic two day brain-melt of hands on intro to event storming in all its flavours of which there are 3:

- Big picture (focus of this post),

- Process modeling and

- Software/design modeling.

We modelled a life like domain (happened to be Alberto’s own company’s domain actually) from start to finish and got it all the way to design modeling. I had heard of event storming before and was roughly familiar with the format and had attempted conducting a session with my team once, but the amount of complexity, nuance and insights that I got bombarded with during the masterclass made me realise I knew nothing about it.

Fast forward to 2024, I have since conducted dozens of event storming sessions now across multiple domains and a diverse set of stakeholders, at work, started taking some of them towards the ultimate conclusion – code and even mixing it with Team Topologies to reorganise teams for architectural agility. Given currently I am focussing on another initiative for a few months, and taking a break from event storming, I wanted to reflect on and share my experience and learnings from big picture event storming sessions. Hopefully it will be helpful for others as well, but if there are tips and tricks I am missing please feel free to leave a comment or two, I am still learning to get better at all levels of this technique.

I find event storming so useful that I’ve even applied it to model the domain for my own side software project that I work on from time to time. You can check out the 2 part series here: Part 1 and Part 2!

Triggers for Event Storming

I have found there can be 3 broad categories of triggers to want to conduct an event storming session:

- Domain exploration: if I am starting in a new domain or a team or I am not familiar with a domain or we are talking about building a new product or starting a new user journey and unlock some new value, a big picture event storming with all relevant domain experts and a few experienced engineers, can be a great way map out the current state, build a shared mental model of the business process and identify the core pain points and opportunities that we want to work on. Building a good mental model of the problem domain you are working on is always a good idea because it allows us to build software that is better aligned with the business and keep accidental complexity low.

- Differences in perspectives: often times domain experts don’t agree with one another, for illustration, one might say, “when X happens we notify Y department and then send X for processing later” and another might say, “No, we actually send X for processing first and if we are not able to process it, then we notify Y department but we shouldn’t be notifying anyone…”. Most interesting differences are those that are about ownership boundaries, one person says they shouldn’t own it, the other counters them. Bringing these differing perspectives under one roof in a big picture event storming is a great way to visualise these differences side by side to what they agree on, get additional domain experts involved and ask some pointed questions to build a common understanding.

- Team knowledge gaps: whenever I ask domain specific questions to engineers, “why does X happen?” or “who is responsible for doing Y?” or “how does this part of the process work?” and I get blank looks, its often an indication of knowledge gaps in our understanding of the domain so before we get to coding, it will serve us well to deep dive into the domain a bit and understand various information flows and boundaries. I have been pleasantly surprised everytime just how much nuance and insights we discover during these sessions that fills in all those gaps.

There is of course no hard and fast on when to and when not to do an event storming session. For example, if the problem space is well understood by domain experts and engineers alike, there is no contention or we are extending some existing feature set of an existing product that fits within existing well understood business process, then an event storming might not really be worth it. Anything broader scoped at the level of a product, a team, a business domain, system boundaries etc, an event storming is more than worth it.

My Big Picture Event Storming Flow

Big Picture Event Storming can be a big time investment across multiple teams and stakeholders so I need to have a certain method to the madness for how I am going to facilitate these sessions effectively. Below is my current set of practices that has evolved over the last 3 years and will continue to evolve but hopefully it paints enough of a big picture (see, what I did there? 😉):

Stash it Up

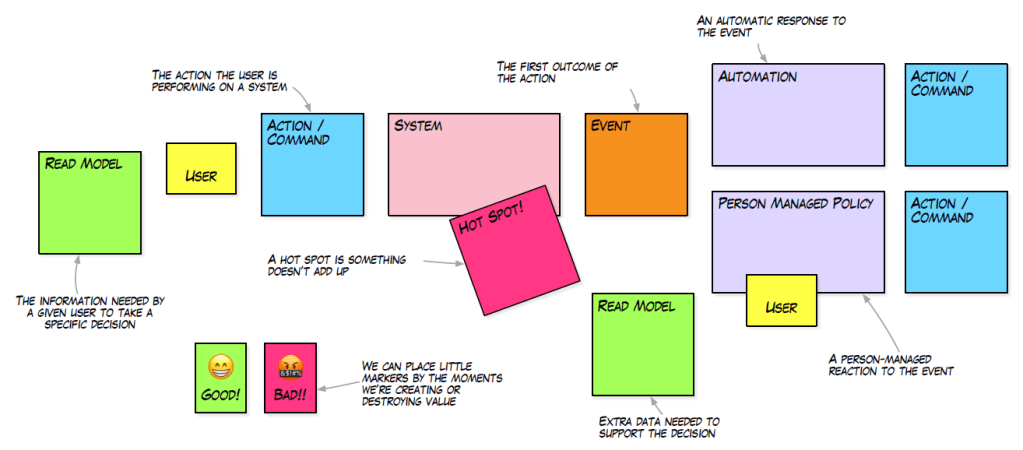

The colour grammar of event storming is important, and I prefer to stick to that. Outside of the core colours, I am free to invent other stickies as I need, so its important that I have enough of all the core colours.

I never want to run out of stickies in the middle of a session and want to make sure that sticky notes and sharpies are accessible to people throughout the session, so I keep my stash fully stocked up and ready to go

Most important stickies you never want to run out of are the orange ones (especially in a big picture event storm) because they represent domain events and we go through a lot of them very quickly compared to other colours. The other colour you don’t want to run out of is maroon ones because they represent hot spots/questions/contention points that are critical for generating new insights. In my view, its better to be overstocked than under and risk running out in the middle of a session.

Get the Right People In

I cannot stress enough the importance of having the right people in the session and making it clear how the session will be conducted (physical office or remote), in order to make it a meaningful investment of everyone’s time.

On one occasion we planned an event storming session months in advance to ensure highest possible attendance, and we made it clear that the session will be conducted in a physical office space so physical presence of everyone (or their substitutes) is required, yet somehow, a couple of domain experts and stakeholders ended up joining remotely which wasn’t going to be effective for the session. We had to drop them out of that session with a possible follow up with them separately.

As a facilitator, I can’t always plan these sessions myself because I don’t always know who to invite, so I delegate to folks like host team’s product owner or manager or someone who knows who will be impacted by the decisions we make or whose perspectives need to be incorporated. One thing I have have made sure we don’t do is mention words like “event storming” or “domain modeling” or “bounded contexts” etc, basically any process related terminology that might intimidate or confuse business participants, in the invite we send to people. Instead we use general words like “brainstorming”, “collaboration”, “learn from you how you work”, “exploration” etc., we can ease them into terminology later.

In terms of the ratio of business participants to engineers, I prefer 3:1 i.e. 3 business participants for every 1 engineer. Reason being, engineer heavy sessions can make it hard to surface domain concepts and flows and we risk getting side-tracked into technical details too soon. I have made this mistake once, it was a catastrophe! Never again!

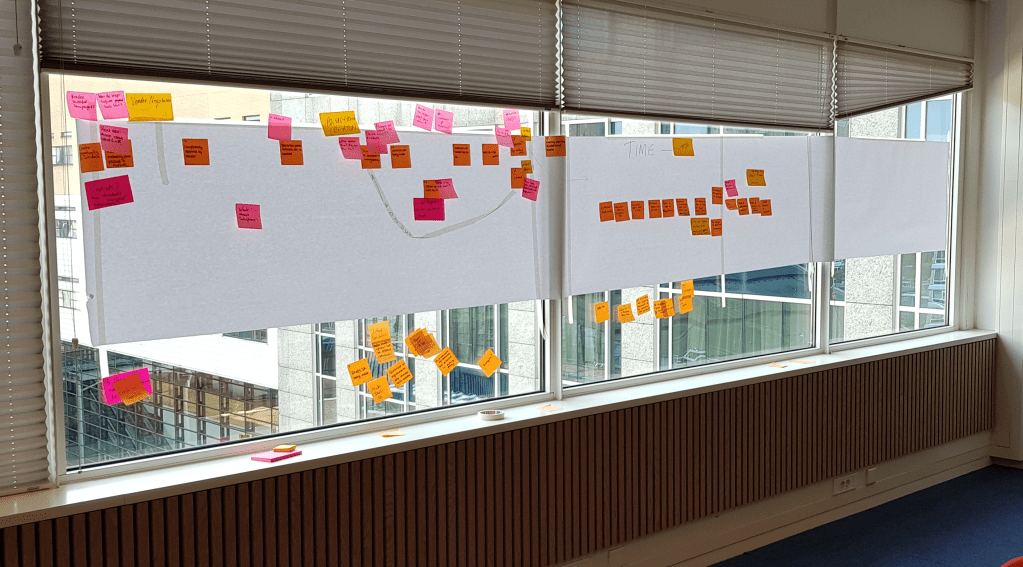

Venue

In my experience conducting the first big picture session in a physical office space as opposed to online, tends to yield better results due to better human relationships and rapport forming between participants and higher bandwidth communication. Once everyone is a bit more familiar with the flow and people, I take subsequent sessions online on Miro where people can join remotely however they want and that usually also works out (less physical exertion). Its important to have the physical event storm digitised beforehand though, best time to do it is right after the first big picture session.

Avoid hybrid session for the first big picture session where some people are in office ready to physically move about and put up stickies on the wall, and some people are joining remotely. Especially in a large group. What are the remoters going to do? yell across the internet to someone to put their stickies up on the wall? What happens when they realise they made a mistake? My recommendation is to get them to come to the office if possible or let them leave the session and pick up the discussion with them separately. This is why its important to make the presence requirements absolutely clear from the get go so people can plan.

“Hack the Space”

The first thing I do on the day of the session, is I check into the meeting room about 5 mins early if possible, and move away all conveniences of a meeting room: tables, chairs, benches, stools etc, as far as possible. This is a collaborative session and I want people to be on their feet moving about, putting up stickies, discussing things and being actively mentally engaged, this is not a presentation where you can kick back, relax for a couple of hours and go home. So chairs are off-limits!

Of course, if someone has special needs or if this is a long session (>1 hour) as it typically is and you want to relax your feet, then by all means take a seat I am not expecting you to sacrifice your well being for this session. I can’t stay on my feet for that long, I don’t expect anyone else either. Sometimes moving chairs and desks away is not possible, but this is where clear instructions can help!

The next thing I do is set up my modeling space on the longest wall/window of the room, this means sticking up a roll of blank plotter paper with masking tape up on the surface:

Benefit of using a sheet of paper as opposed to sticking the notes directly on the wall, is that at the end you can take down the paper and take it with you to digitise later. Also allows you to draw and scribble on the modeling canvas if you need without worrying about marking up the wall surface with a sharpie.

Quick Intro and Goal

I want to start on time regardless of whether or not all attendees have joined in, waiting past the scheduled time is unfair to punctual folks and is expensive. I kick off with short personal intro (name, role, years in the org…nothing more), the goal of the session and a brief intro of Event Storming, so something like:

Our goal today is to understand how we process customer orders placed via the webshop end to end. We’re going to do this by writing stickies for all the critical things that happen in that flow in sequence. Time permitting we would then like to understand the biggest pain points in the flow that we can help address or new opportunities that we can help unlock.

Whilst the exact formulation is not relevant here, let’s dissect the structural components of this intro:

Goal of the Session

I always start here, its important to make the goal as specific as we can, e.g. asking “how do we process orders” can be too broad, are we talking about customer orders or B2B orders or are we talking about purchase orders which is something else entirely? are we talking about webshop orders or store orders? Sometimes we manage to narrow it down in the session but I prefer to have it clear from the outset right in the invite, so we don’t waste people’s time in the session.

An extended goal of every event storming, has to be to understand the pain points that need to be addressed or new opportunities to be unlocked, may be we will build new software for that or we might just propose changes to the process. People are generally very nice and they want to help you understand their job which benefits you, but its also important that there is something in it for them as well. Giving them an opportunity to voice their pains is the least we can do, we may not solve all the problems for everyone but at least we have made them heard on a bigger stage and acknowledged them.

Visualising What?

I used to say, “…we are going to visualise all the (domain) events in the process in sequence…” but I’d often got blank looks from the domain experts and stakeholders, like, “what events?” So these days I just use the general term “things” instead and I give them examples of sequence of events from daily life (e.g. I woke up this morning, then I drank coffee, then I got ready for work, then I left home, then…etc). There are other examples that I also use, e.g. a novel is a sequence of events that tell a story, if you want to understand the ending you need to understand how it got there. Or another more gruesome example, if you are investigating a crime scene or an air crash, you need to work your way back to understand the events that led up to the conclusion to understand what actually happened.

Or better yet, something closer to their work domain (e.g. customer placed an order, then customer order was confirmed, then packing started, then…etc), and then sometimes the light bulb goes off. Basically <noun> followed by <past-tense verb> (or more accurately past-participle). With a domain example, I try to be careful to not taint their thinking with my shallow understanding of their domain so I will show them this kind of sequence as an illustration and then throw it away.

Over the years I have learnt that this pre-emptive explanation doesn’t always help, when they are in the thick of visualising or explaining something, people default to their own usage and interpretation of the language (especially in cases where English is not their main language). And that’s ok, that’s where I as a facilitator can help the group optimise the language later on in the session so we don’t have to spend too much time explaining upfront. We’ll get better by doing, not explaining.

Rules of Engagement

Event Storming is supposed to be a very organic human oriented exploration process so I want to preserve the original spirit as much as possible. However, human practicalities of time and energy constraints means that I need to have some minimal rules in order to make the best use of everyone’s time and energy, therefore I have created 3 simple rules for these kinds of big picture event storming sessions:

- Focus only on the business process and concepts. No technical talk or solutionising allowed just yet

- Give everyone time and space to put up all their stickies without distracting them

- Visualise all side discussions on the modeling surface, or don’t have them (i.e. the side discussions)

Its my job as a facilitator to enforce these rules strictly throughout the session, we are here to build a cohesive mental model of the current problem space so we can solve right problems and solve them right, and we have asked for a lot of time investment from a lot of people so we are not going to waste any of it in discussions that are not relevant or that drag the session into a rabbit hole. If required, we can plan more focussed sessions separately to delve deeper into specific areas but for now, let’s build a big picture view first.

In total I don’t spend more than 10 mins on intro (personal and process) and rules.

Throughout the session, participants are free to weave in and out if they need to take a call, drop into another meeting, toilet breaks, get a drink etc. We are going to be here for a few hours, so its important to keep the presence flexible. A requirement of mine is that you at least ought to have put your set of stickies up on the wall, before you disappear. That way we know we are not missing out your perspective.

And I also put in a 10 min break at about the half way mark for sessions longer than 1 hour, and ensure we know where to pick up when we come back.

Show Me the Events

Now its time for all the business experts and stakeholders to write up the event stickies based on how they understand the process and stick them up on the modeling canvas in a time ordered sequence from left to right. Engineers can also put up events if they want, however, engineers are mainly there to listen, ask questions and take notes.

I tend to time box this activity to about 10 mins to start with(regardless of the number of participants), and if people are still writing their stickies and need more time at the end of that then I can extend the timebox by 5 mins with only 2 such extensions allowed. So maximum timebox is 20 mins and minimum is 10 mins though through all these years, not once we needed more than 15 mins. If people still need more time, either the goal of the session is not well understood or people are trying to cram too much in.

Enforcing rule 2 is critical here, don’t distract people who are writing their events by challenging them or correcting them or moving their stickies around or having lengthy or loud siloed discussions about them. If there are duplicate stickies for certain events, let them be for now. We will get a chance to clean everything up and enforce the timeline properly, later. If there are questions already, take the maroon stickies, write your question or contention on it and stick it up close to the relevant event(s) and I will make sure we come back to it later.

In one of the sessions I noticed a tendency of a small group of people to get stuck in analysis paralysis because they wanted to capture everything completely (all edge cases, side flows etc.) so they were essentially violating all the 3 rules amongst themselves. After about a minute of letting this go on with none of their stickies on the wall, I decided to intervene to break the deadlock and had them put whatever they had up on the wall and additionally, handed them a few maroon stickies each to note down the challenges or unclarities that they want to resolve later. This way we move forward without derailing the session and without ignoring or forgetting potentially critical questions.

Tell the Story

According to me, this is perhaps the most important and the longest step of the process right here with no inherent structure. Everyone’s told their version of the story, now we will attempt to do the impossible – get people to agree on a single cohesive version of it😀. Additionally, we will deduplicate events and enforce the timeline “hotspotting” or clarifying the hotspots we can and marking out first draft of sub-domain/bounded context boundaries, as we go. This is where a lot of things happen and not necessarily in any prescribed sequence. I tend to step in and out of discussions to break stalemates, enforcing rules, ask the question etc but as a facilitator, I mainly let the participants hash out the nuances and its taken me a lot of trial and error to get some semblance of structure. I want to avoid becoming too much of a participant in the session than the facilitator, especially, when its a domain that I might have some familiarity with.

Walkthrough the Storyboard

At this stage, I ask for a volunteer domain expert to walk us through the timeline of events in front of us from left to right and describe what’s happening from start to finish. A trap here is that sometimes people will just read the stickies out loud rather than describing the flow. Simply reading the stickies doesn’t help with understanding or clarifying, but if you describe a bit about why this event happens, who takes the action that triggers the events, what might they do in exceptional cases etc, then we start to form a more holistic view of the current state and we have more information we can visualise. Generally I ask for someone who understands the process the best, because they tend to have an instinctive feel for the flow, they don’t need to read out all the stickies they can very organically describe the process.

Compare “first order is placed, then order is confirmed, then order is packed….” with “Say a customer is looking to buy a washing machine, when they find something they like they will place an order for it. When we receive the order then we need to make sure we have enough stock of it to fulfil the order, and if so then the order is confirmed otherwise the order is rejected. In both cases we notify the customer what’s going to happen and we….”.

Which one reads like a more relatable and organically told story?

My Role During the Walkthrough

As a facilitator, I tend to also play the role of what Alberto calls, “the scribe” i.e. a person who’s listening to the walk through and any discussions that might shoot out as a result, and documenting necessary information. This information could be: missing events, or reframing or reordering of events or may be hotspots to come back to afterwards, additional contextual or scale clarification (e.g. during the walk through the story teller might casually mention “we review around x approval requests per day” etc which I would note down and stick up on the wall), just basically additional information that can enrich the model.

My flaw here is that sometimes I stretch myself too thin and I’d be walking with multiple coloured stickies falling out of my hands as I fumble to scribble on them to capture what people are saying. This is a not a good idea, because I start to become more of a participant than a facilitator at the risk of loosing focus on the big picture and keeping the group on track, and the point is to get the people to participate, so nowadays I ask one or two people to help me out with scribing.

Sharing the scribe role, also frees me up to challenge assumptions and ask additional questions and help the group deduplicate events. I aim to not have the story teller be interrupted too much and let them complete at least one pass of the walk through and then we can do another round of refinement walkthrough, where I can assume the role of the story teller (as a relatively impartial, external person) and tighten any loose screws in the emerging model, so to speak.

Secondary Walkthrough

This second walkthrough is not necessarily a standard event storming step, but there are no rules against it plus, walking a complex flow a couple of times just helps crystallising and refining what was said before and in my experience clarifies the model a lot more. Let me give a few categorised examples of advantages of this step:

Surfacing the Domain Concepts and Reasons

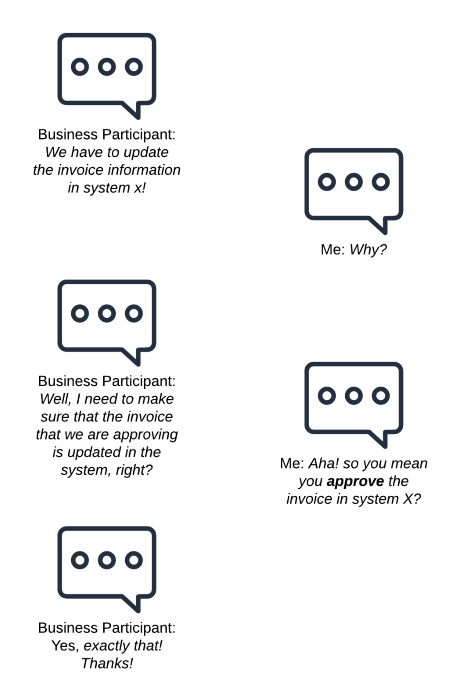

For example during this second walk through I once saw an event called, “Update system X with new contract details”, so I challenged the group to clarify the intent behind updating system x and they said something like, “oh we are updating the contract details to indicate its approved”. So I refactored the event name to something like, “Contract approved” and asked them if that still made sense and it did.

I find many participants tend to describe a lot of things in terms of the technical tools they use to do something instead of talking about the reason for doing something using that tool.

For example, “we update the Google Spreadsheet with details of X and then we send emails with the relevant info attached. Later we check the reports in Looker to make sure information is up to date…”. Sometimes they go one step further and start talking about “updating data for Y in Oracle” or “data for Y in Oracle has to match what’s in Big Query”…

My observation is that some people tend not to think very deeply about why they are doing what they are doing, they have been told to do something in a certain way using certain tools, and they just stick to it. Event storming is probably the first time they are being asked to think about the why and that almost always leads to new insights. E.g. once one participant was describing how they update some information in the legacy ecommerce system as a part of their workflow, and when asked why, they said, “I was told to! I don’t really know why!” and then additional information came to light when someone else said, “well, we don’t use that information from that screen anymore so you don’t need to update it anymore”. So essentially, this nice person had been wasting their time doing something no one used, but thanks to this collaborative thinking process we now know and can do something about it!

My other observation is that after a while, the tools people use become so synonymous with the business process that they can’t describe the process any other way. For them “updating a record in a system” is the business process, so I have to probe deeper into their minds to uncover the domain gems that are hiding behind the cruft of technology.

Sometimes its just hard to surface that clarity in the moment so it might take additional enquiry, but I enjoy this part, to me this is what tech-business collaboration should look like where we can use a common language of the business to create good enough models of the what and why and the technology itself just becomes a how. This is also why I enforce rule 1 very strictly, especially when there are other engineers or product owners in the room, I have had to stop discussions about “stored procedures, database triggers, checkboxes, services” etc to stop the underlying domain concepts suffocating under all that technology tear gas, at least in the big picture event storming sessions. This is also why I make sure that we are being specific with the events we visualise and not contaminate the language with technical terms.

Refining the Narrative

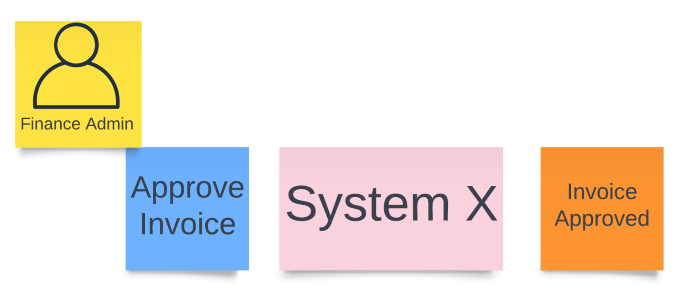

In a big picture event storming you are only meant to focus on events, but given how the systems have become an integral part of how business users engage with business processes, I tend to introduce other colours of the colour grammar in the big picture session so as not to lose that context. E.g. if somebody writes an event sticky:

I will split that up into 4 different stickies: a role, a command, a system and an event. And now we have a bit more of a narrative of who is doing what, where and what’s the outcome.

Generally I prefer to do this split then and there to make it visible for everyone, but sometimes we have a lot of ground to cover so I will add a hotspot sticky as a reminder to split it later on a digitised version.

Settling Disputes

Another one of my favourites is when two sets of people disagree on whether or not an event is relevant or they are just not sure but feel as though it could be an event. The way I resolve this usually, is by covering the event sticky with my palm and asking them, “Does the flow of the process still make sense or does removing that event adversely affect the business process? What critical information will be missing that might make it harder for you to do your job well as a result?” In most cases, turns out, that event is not needed at least not for now so I would move it out of the storm and stick it around the edges of modeling canvas (not throw it away) in case we want to revive it later.

If we don’t end up reviving these events later, then they’re consigned to the rubbish bin and the model is better for it, and I can’t really recall when was the last time we revived a discarded event (may be once or twice). I suspect this happens because people are still trying to figure out events in their heads and they’d rather put more up than less, there is no right or wrong here. In the end what I am aiming for is that we largely agree on the flow, all critical events have been captured (including any systems, roles, data etc), and preferably all the hotspots have been resolved. Its entirely possible that in later stages a disputed event will be discussed and its fate decided so I leave that possibility as a plan B.

Boundaries

This is one of other most critical parts of the process – identifying initial boundaries between sub-domains/bounded contexts.

During these walkthroughs, sometimes prompted by participant questions or mine or of their own accord, the story teller will point out where does the transition of responsibility happen from one context to another. I will also be watching out for signs of language changes and conceptual differences in the business processes or end of one part and start of another or I will see small groups of people huddled around specific parts of the storm.

All these are good indicators of early boundaries. They may not be right, matter of fact very likely they are not right that’s why we are here doing all this event storming stuff, but its a good place to start discussions about boundaries and see if they need to be clarified.

As a facilitator the moment I see these hints of transitions or separations, I run over and stick a vertical strip of masking tape along the transition line and put a sticky note up on top to indicate the name of the boundary. The events on these transition lines are my pivotal events i.e. events that indicate a change in the responsibilities and purview in the flow or the end of one distinct part of the process and start of another and as such might be events that other parts of the business might be keen to know about. For example, in the illustration below the dark orange stickies (one with the orange vertical lines) are the pivotal events because note how the language and conceptual focus is shifting from purchase order to stock and deliveries which invoicing and purchasing domains need to know about.

The Purchase Order Submitted event is an event that signifies an important step of the purchasing flow, a checkpoint if you will, after which warehousing needs to start preparing for delivery of the ordered stock. Likewise other pivotal events in this flow might signify an important juncture in the flow that is relevant for other parts of the business.

The aim here is to have some groupings of related stickies where each group might represent either a sub-domain or a bounded context that we can map to a distinct part of the business process and name it. This will have implications for code and software architecture down the line.

There can be a lot of nuance in boundary discovery and things are never very cut and dry, so I tend to keep coming back to this part regularly in the coming weeks and months, and use it as a basis for further discussions with domain experts and engineers.

Pain Points and Opportunities

After all that knowledge crunching and modeling, if I am lucky and as a facilitator have been keeping everyone on track, then we will have time and energy left over to talk about the pain points or opportunities. A pain point is an opportunity but an opportunity is not necessarily a pain point e.g. reducing the number of reviews required for an insurance application might be an opportunity to simplify the process (and the corresponding software design) but it may not necessarily be something that makes people’s life difficult or reduces the flow of the system as a whole. An example of pain point could be one person having to enter information about supplier contracts in multiple systems and having to pull information/approvals from multiple business units. May be the current boundaries are inappropriate that’s causing a bigger WIP for this one person and slowing things down. Once again, no hard and fast rules here in my view, I have found my participants to be fairly vocal about what makes their job harder and that makes my job of identifying pain points a bit easier.

The whole big picture storm can be quite large and surface a lot of complexity, which is good, but we obviously can’t solve the whole thing so we want to start solving the biggest pain points first. This is why its important to agree on the most painful parts of the flow first and start there.

I do this by having business participants vote for their favourite pain points or opportunities, by putting a small arrow sticky on the area or the hotspot they feel most strongly about:

In order to create focus and fairness, I give each participant 4 votes in total (2 x pain points, 2 x opportunities). In the end the pain points and opportunities with the most votes, become the starting point for the next steps. Typically the next step would be design level event storming with the engineering team where we can add additional colour grammar to the storm (commands, read models etc), ask more focussed questions to the domain experts and really start to converge onto a solution model. But I am getting ahead of myself, that will be part 2 of this post which might take me a while to get out.

Concluding the Big Picture Session

At the end of the session, I thank everyone for their time and also make sure to create an opportunity for subsequent follow up sessions by asking if they’d be willing to help us in a session like this once again if we have more questions, and people having seen what this process can do are more than happy to help out again. I have often got feedback that they really enjoyed the “on the feet” thinking aspect of this process, the collaboration and the amount of complexity and questions we managed to surface that they didn’t know existed.

We take pictures of the storm to digitise them on Miro later and then take down the modeling surface. Make sure we restore the meeting room to its original state, so throw away any trash and tidy the place up.

I also recommend the hosting team to not get into solutionising right away but step away from the storm for a coupe of days to let the “dust” settle and brain calm down, and then come back to it with clear eyes. I have found, right after the big picture session is exactly the worst time to jump into solutionising because you might have been too swayed by something during the session or might not be thinking holistically. Step back, digitise the storm and then review it with the team afterwards.

This concludes the first Big Picture Event Storming session for me.

In Closing…

Big Picture Event Storming is often called a “chaotic exploration” or “divergent exploration” process and is crucial to form a good mental model of the current state of the business processes. It uses some very simple low tech tools with very few but important rules. It can be done both at the whole organisation level or at the level of specific parts of the business, though I have not yet tried the former. It requires time and effort investment across cross-functional roles to allow forming a shared model of the reality (and it is a model, an abstraction of reality, not reality itself).

If you have an environment that encourages learning, and close collaboration of business and engineering, conducting these sessions might be easier than if business/domain experts are rarely available to answer questions or not co located enough to be available for in office sessions. Or if software engineering teams are just viewed as magic feature factories.

Its not business stakeholders’ mental model that goes into production, but developers’ assumptions.

Paraphrasing Alberto Brandolini

Its important to see this kind of collaboration between business and engineering as a crucial step to breaking silos and ensuring the mental model of the business experts is the mental model of the engineers is the model that’s captured in the code we write. Its this alignment that keeps the communication friction between business and engineering low which allows engineering teams to be embrace change, be fearless and create value all the while continuously improving and learning.