In part 1 I talked about the key aspects of my TDD practice from a workflow pov, in this final part I will talk about the more tricky aspects of TDD – scope and design.

Once again, I am using the canonical definition of TDD as laid out by Kent Beck, also his book TDD By Example and, Jason Gorman’s excellent tutorial on TDD. Another book that is quite influential in TDD/BDD space is the GOOS book. For elements of structural design, I am going to be referencing some ideas from the Structured Design book. In my view these should be mandatory study material in software engineering because these ideas are timeless.

Tests Test Behaviour, Not Implementation

For me, “behaviour” exists at different levels of granularity i.e. at the top level behaviour is about what part the system plays in a business domain, at low levels behaviour is about how the system interacts with other systems in order to accomplish the top level behaviour. For example, a system that at the top level allows customers to place orders and get food delivered at their doorstep might at low level achieve it by notifying the kitchen to start preparing the food, looking up delivery driver availability, allowing the customer to track their food delivery etc. All these are “observable behaviours” (i.e. their outputs can be inspected and verified by an external entity – a human or a system), and therefore both top and low level behaviours need to be covered by tests.

“Implementation details” on the other hand are either structural elements of the system (e.g. I’ve decided to decompose some behaviour into these 2 classes, as opposed to those 3), or they are infrastructural components (e.g. a relational database of a certain brand, or a specific broker technology or an e-mail service provider etc). They are internal because whilst they enable the observable behaviour, they don’t (or shouldn’t) impact it or put constraints on it. This is what allows one relational database to be replaced by another, or one email service provider to be replaced by another. Any shocks are to be absorbed by the edges of the system where we integrate with them.

For example, when pairing with my colleague, we initially wrote code to pass the failing test for the right reason. Whilst doing so we took shortcuts, we complicated dependencies, we put responsibilities in odd places…we made a mess to get to a passing test (immensely simplified for brevity):

| public class DoSomethingUseful(ISomethingRepository somethingRepository, IFlubberAppender flubberAppender) | |

| { | |

| public void Execute(SomethingId somethingId) | |

| { | |

| //...do something with ISomethingRepository | |

| //...do something with low level domain objects | |

| //...do something with the domain objects to shape | |

| // them into Flubber compatible object, and finally.. | |

| flubberAppender.Append(...); | |

| } | |

| } |

But once we had a passing test and we had made a commit we then refactored to remove duplication and hardcoding, pulled related code into static functions, moved these related functions into a separate class, added appropriate dependencies there etc because now we had the safety of a good regression test, which resulted in the final structure that looked like this:

| public class DoSomethingUseful(ISomethingRepository somethingRepository, IFlubberAppender flubberAppender) | |

| { | |

| public void Execute(SomethingId somethingId) | |

| { | |

| //...do something with ISomethingRepository | |

| new FlubberService(flubberAppender).AppendFlubber(...); | |

| } | |

| } |

We created FlubberService as an internal structural element to encapsulate some common processing but from the pov of the test, nothing changed because the interface exposed to the test was still the DoSomethingUseful interface. We instantiated the service within the use case, passing in the IFlubberAppender interface as dependency to the service. FlubberService therefore didn’t have to have its own tests. It took us a couple of hours to do this refactoring and tests were still green because the tests were connected to the observable behaviour of the public API, not its internal structure (i.e. the FlubberService). We could refactor this class into 3 smaller classes if we need to, the tests will still pass and we won’t necessarily need to write additional tests for the smaller classes. This kind of decoupling from implementation details allows me to have meaningful tests and refactor safely.

⚠️Using

InternalsVisibleToin .NET to expose internal types and behaviour to tests is an example of coupling tests with implementation details. Either its public or it should be tested via an already exposed public interface or, module boundaries need some work.

To Mock or Not To Mock, That’s… a Meaningless Question

Often the advice on the interwebs is to “avoid mocking” because “it couples your tests with the implementation details of the code”. To me this advice is too broad and lacks nuance.

Based on how I have defined “behaviour” and “implementation details” above, we didn’t have to mock the class I talked about in the previous section because its an internal dependency so I can just new the real one up where I need it without dependency injecting it, I’d still inject external dependencies the class itself depends on. If we had written a test for the class in isolation, that would indeed be coupling my tests with the internal structure of the system because if I refactor that one class into 3 classes without impacting the top level observable behaviour of the system, all these isolated tests will still break. Its this kind of coupling that discourages refactoring and impedes flow that people often incorrectly blame on TDD itself.

However, mocking (one of many types of test doubles) is completely relevant when the top level observable behaviour is composed of low level interactions with multiple external systems and I don’t control how they behave. In these cases, wrapping the external dependency behind a domain specific interface (“port” in Ports and Adapters terminology) such that I can a) write top level behaviour tests without getting into the rabbit hole of the external dependency just yet, and b) I can simulate specific faults and inject errors to see how my system deals with them, is perfectly valid. For example, I might create an interface to abstract persistence operations and create a test double of that interface that throws a application specific ConcurrencyException and write a test to assert how the caller of that interface handles it.

Point being, collaborators are an important part of the overall observable business behaviour of the system. In object oriented terms, these are objects communicating with each other by passing messages so it makes sense that our tests cover those communication pathways. For example, when my system makes an HTTP call to another system, does the outgoing request have all the required information (headers, query strings and body)? does it retry transient faults correctly? does it use caching properly? Basically validating my system against the contract of the external system and my own handling of its responses.

Question is should I just write one test that covers everything end to end or should I write separate tests for the low level behaviour? I think the answer has to be “it depends”, if writing one end to end test doesn’t complicate the understanding of the test and refactoring of the system, then writing one test is fine (less overhead and higher confidence). Otherwise, I’d separate the top level behaviour test from the low level behaviour tests, verifying at the higher levels that the appropriate collaborators at the low levels were invoked in a particular way with expected information. The low level tests will then target the external dependencies using test doubles (either high-fidelity e.g. containerised databases, queues etc or low-fidelity, in memory test doubles if that’s the only way).

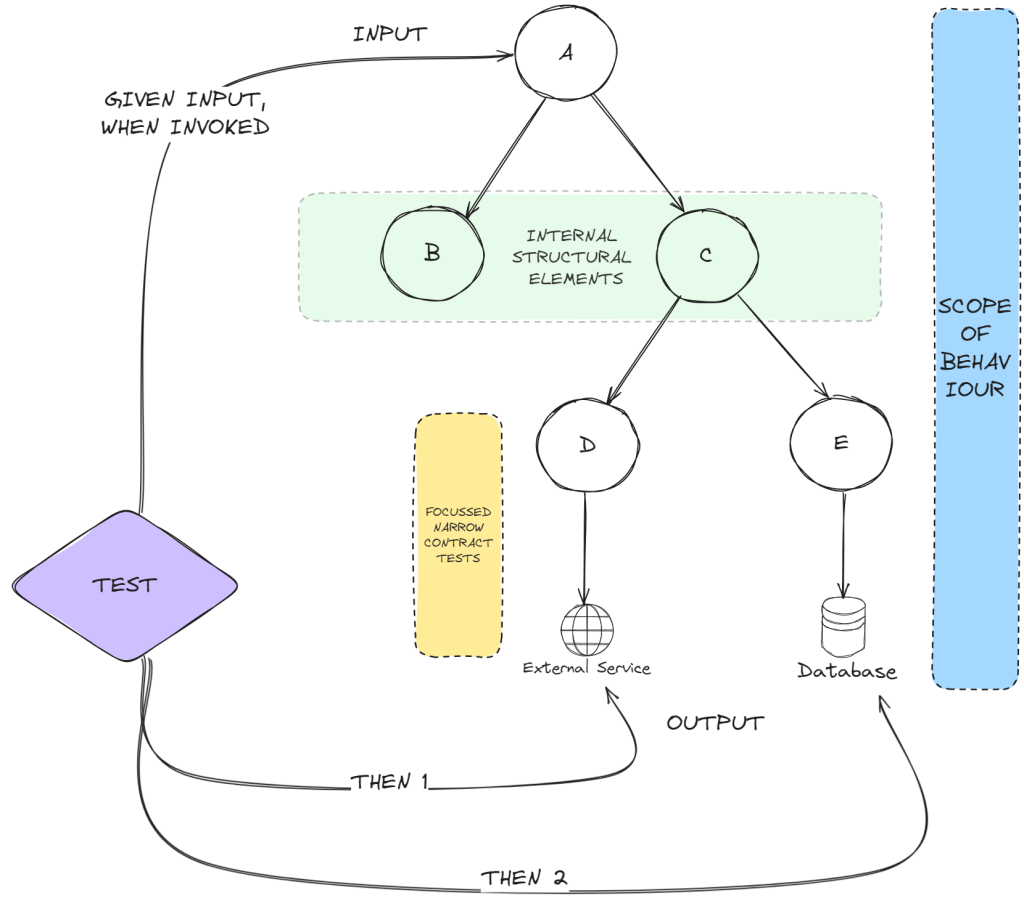

In the illustration above, A is my SUT at the top level, B and C are internal structural dependencies (highlighted in green) and D and E are adapters to the outside world that implement application specific interfaces and translate between my system and external.

I might start with a single test and assert at the lowest level of observable behaviour creating high-fidelity test doubles as appropriate, aka:

- Given some input, When A is invoked, Then D and E produce expected output

If writing a single end to end test would be hard to reason about and maintain (which can happen given enough complexity), then I will split the tests between infra agnostic behaviour using low fidelity test doubles (top level) and infra specific behaviour using high fidelity test doubles if possible (low level – highlighted in yellow), aka:

- Given these arguments, When D is invoked, Then the outgoing request looks like this (additionally write failure handling cases)

- Given these arguments, When E is invoked, Then the database records are affected this way (additionally write failure handling cases), and

- Given some input, When A is invoked, Then interface for D is invoked once with these arguments AND interface for E is invoked once with these arguments (additionally write failure handling cases)

Couple of things to call out here:

- B and C are not test doubled because they are my internal structural elements so I want to use their real (and only) implementations.

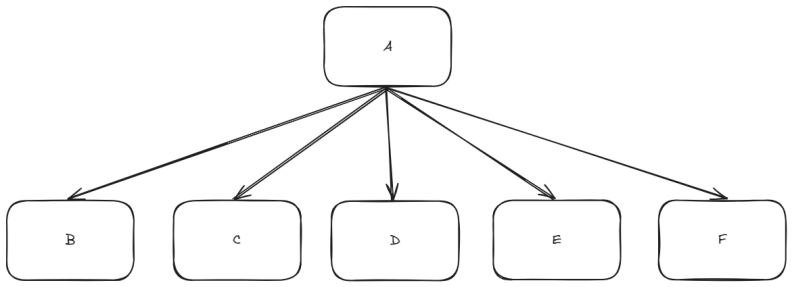

- Too many collaborators at one level, could be a design smell (aka “pancake design” or “micro-manager design” in Structured Design terminology). May be I’ve taken on too many dependencies and I need to reduce or restructure them to create a deeper hierarchy than a shallow one. This could complicate tests as well.

- Testing at too high of a level could make tracking down defects harder, I wouldn’t know which object(s) in this hierarchy is/are not behaving correctly. I might need to either debug or write focussed isolated tests for these low level components. Testing only at low levels, doesn’t give me confidence in the overall behaviour either. So I need a mix of both! Decomposing code and tests is a reaction to certain high levels of complexity and cognitive load, if complexity is manageable there is less benefit to be gained by decomposing.

- Care must be taken if test doubling an externally owned interface in tests (e.g. in .NET

IDbConnection,IAmazonSQSetc. interfaces are exposed by their vendors), because I don’t control their evolution or implementation so my double is going to be a very weak representation of the real thing. At best I can only verify that I passed all the required arguments to the API correctly, whether or not it will work at runtime will not be a part of this test. Higher fidelity test doubles like containerised dependencies might be a better option in these cases. In some cases creating a double might not even be possible e.g.SmtpClientwhich doesn’t expose a test double friendly interface.

TDD != Design && TDD == Design

Here’s Kent’s thoughts on “TDD is not an X technique, but a Y technique!” type reductions. TLDR; its all of the above!

People often argue that TDD doesn’t help with design, and in a way they are right, it can’t on its own. It only slows me down enough to actually spend time thinking about the design, and how can I improve it, safe in the knowledge that the test suite will catch regressions and allow me to get out of the mess quickly (git reset --hard). I still have to do the work to create a good design.

A problem I have encountered in the past, is that I’d write tests for the design that I have in mind what Jason Gorman in his tutorial calls, “Design Driven Testing” (DDT) i.e. I need a use case called SubmitFoo which needs to take dependency on FooService, so I need a test for that and then a dependency on FooPublisher so a test for that…etc, instead of what the GOOS book calls “pulling the design into existence” guided by tests i.e. let’s write the test and have the assertion require a dependency to be introduced incrementally without prematurely refactoring into a particular structure!

One might wonder, “well, what’s the difference if you end up with the exact same code?”.

First off, I don’t like to be that reductive, how someone arrived at a particular design, what decisions they made, what trade-offs they accepted and why, are more important than the resultant code itself. These are the hard earned learnings that we build over the years of our career, that we need to teach and pass on to the younger crop of engineers. AI can write code, but being good at these “context sensitive squishy” things and critical thinking that not just solves problems but redefines a problem better, is a big part of our value proposition as human software engineers.

Back to the question, the difference in my view is that of mindset, in DDT my focus is on writing code to build a working feature quickly. In TDD, my focus is additionally on creating a usable API and also on breaking the code I write by thinking through what could go wrong and design for those eventualities. So in DDT I am behaving purely like a coder but in TDD I am behaving like a designer and a tester. In DDT I mainly am solving a coding problem, in TDD I am solving a design problem and finding additional problems that impact the overall solution but people often don’t think about. Now, an experienced designer can probably operate both ways and come away with no significantly different a design (functionality wise or quality wise) but as an experienced designer myself, I sometimes surprise myself with edge cases that I considered in TDD mode but not when in DDT mode (or when I am pairing with someone less experienced and they challenge some aspect of the design that I thought was obvious, the ensuing discussion alters the design away from what I had in mind, for the better!). DDT in my view therefore, has a higher likelihood of resulting in over-engineering or gold plating or even missing certain paths entirely. Its also likely that the tests are coupled to the implementation details and smallest refactors could break multiple tests.

Design constantly evolves, I design for what I know today whilst not cornering myself against what I will know tomorrow and I still keep my experience based design options handy. People often associate this future flexibility with creating lots of abstractions upfront because that’s what keeps things “loosely coupled” and I’ve made this mistake myself. Instead, I think its primarily about not making premature design decisions (i.e. being able to defer certain design decisions), because I don’t know if any trade-offs induced by my today’s decisions, will be acceptable tomorrow in an evolved context. I won’t know what a good design looks like or could be until I’ve seen a bad one first and TDD allows me to take the design from “bad” to “good” (or rather, “inadequate” to “appropriate”) safely.

In Summary…

This has been a reflection of my own practice that’s continuously evolving and as a report of an experience that’s been quite different from the folks who claim that “TDD doesn’t work” for all the various reasons. I have certainly seen the pain points of misusing and misinterpreting TDD because I have been through them myself, including treating TDD as some kind of magic dust that will on its own improve the quality of the software I build. Fearing refactoring because “so many tests break” or all the tests passing yet the behaviour is broken or vanity control metrics like x% code coverage etc. And given the amount of discourse we have on this topic in the community on a regular basis, I think there are always going to be challenges in people’s practice.

TDD (and software design too) requires critical thinking, communication, discipline to not forget the refactor step, and deliberate practice but there is also a lot of room for pragmatic decision making without the stress. Hopefully the more people share how TDD works for them, the more balanced and well-informed discourse we can have on this subject, the more value teams might get out of TDD, and perhaps that can help advance the state of the art in the industry. My skeptical brain is screaming at me so I will stop here. 😉

Until next time! 👋Wish you all a fulfilling 2025! 🎆